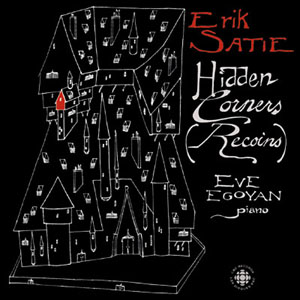

“Recoins (Hidden Corners)” works by Erik Satie (CBC Records)

2001 Earwitness Records (MVCD 1153)

Download: iTUNES CD BABY AMAZON BANDCAMP

Reviews: Sound Advice (CBC Radio) / Gramophone Magazine / Other Reviews

|

1.

|

||||

|

2.

|

||||

|

3.

|

||||

|

4.

|

San Bernardo (1913) 01:02

|

|||

|

5.

|

||||

|

6.

|

||||

|

7.

|

||||

|

8.

|

||||

|

9.

|

||||

|

10.

|

||||

|

11.

|

||||

|

12.

|

Profondeur 01:38

|

|||

|

13.

|

||||

|

14.

|

||||

|

15.

|

||||

|

16.

|

||||

|

17.

|

||||

|

18.

|

||||

|

19.

|

||||

|

20.

|

Ogives I 02:14

|

|||

|

21.

|

Ogives II 02:35

|

|||

|

22.

|

Ogives III 01:43

|

|||

|

23.

|

Ogives IV 02:37

|

|||

|

24.

|

Trois Nocturnes – I 02:49

|

|||

|

25.

|

Trois Nocturnes – II 02:03

|

|||

|

26.

|

Quatrième Nocturne 02:32

|

|||

|

27.

|

Cinquième Nocturne 01:36

|

|||

|

28.

|

Sixième Nocturne 01:26

|

|||

|

29.

|

Valse-ballet Op. 62 01:42

|

|||

|

30.

|

||||

|

31.

|

Deux Choses II – Poésie 00:42

|

|||

|

32.

|

||||

|

33.

|

||||

|

34.

|

||||

|

35.

|

||||

|

36.

|

||||

|

37.

|

||||

|

38.

|

||||

|

39.

|

||||

|

40.

|

||||

|

41.

|

||||

|

42.

|

||||

|

43.

|

||||

|

44.

|

||||

|

45.

|

||||

|

46.

|

||||

|

47.

|

||||

|

48.

|

||||

|

49.

|

||||

|

50.

|

||||

|

51.

|

||||

|

52.

|

||||

|

53.

|

||||

|

54.

|

||||

|

55.

|

||||

|

56.

|

about

Erik Satie (1866–1925) remains one of the most bizarre and fascinating composers in the history of modern music. Indeed, he did much to shape its course through his influence on the composers of Les Six, and later John Cage, who declared in 1958: “It’s not just a question of Satie’s relevance. He’s indispensable.” Like Fauré, Satie’s music shows constant renewal within an apparently limited textural range, and he also refined his musical expression to its bare essentials in later life by giving it greater contrapuntal strength. But there the similarity ends, because Satie remained a left-wing iconoclast throughout. He entirely rejected the nineteenth-century concepts of Romantic expressiveness and thematic development, being the first to repudiate Wagner’s consuming influence on French music. He by-passed “impressionism” and the beguiling orchestral sonorities of Debussy and Ravel, and his art derived more from painters (especially the Cubists) than from other composers.

First and foremost, Satie was a man of ideas, a precursor of total chromaticism (virtually serialism) and minimalism (in Vexations of 1893), the prepared piano (in Le Piège de Méduse in 1913), neo-classicism (in his Sonatine bureaucratique of 1917), and even muzak (in his Musique d’ameublement of 1917–23). Simultaneously he pursued his uncompromising inner path towards simplicity, restraint, brevity and clarity in a way that was essentially French, or, in Satie’s case, Parisian. He remained true to the compositional aesthetic that he notated in 1917, and in essence his art, like Debussy’s, derived from melody, though in Satie’s case this had to remain in direct contact with its popular roots. “Do not forget”, he advised, “that the melody is the Idea, the outline; as much as it is the form and the subject matter of a work. The harmony is an illumination, an exhibition of the object, its reflection…One cannot criticise the craft of an artist as if it constituted a system. If there is form and a new style of writing, there is a new craft.” And in his piano works, mostly assembled from series of motifs (“Ideas”) in jigsaw-puzzle fashion, Satie demonstrated how this could be achieved.

In 1897, Satie experimented briefly with rhythmic and textural flexibility, and the Danses de travers offer an early example of minimalism in which all three slow, quiet dances share the same rhythm, texture and melodic shapes, and are not easy to tell apart. Possibly Satie had the arpeggiated textures of Schumann or Fauré in mind here. The Petite ouverture à danser is in fact another in a series of Gnossiennes, whose strange, undulating melodies were inspired by the Romanian folk music Satie heard at the Exposition Universelle in 1889.

In Satie’s “humoristic” piano sets of 1912–15 the pieces are accompanied by stories or comments to amuse the performer. This process reached its artistic zenith in the twenty-one Sports et divertissements of 1914, a miniature gesamtkunstwerk of immaculately calligraphed musical cameos, accompanied by original prose poems and humorous, Cubist-influenced drawings by Charles Martin. Satie forbade his texts to be read aloud and their ideal performance would be one in which scores, texts and drawings would be projected onto a screen during performance. Lastly in this prolific period of over sixty varied piano pieces come the Avant-dernières pensées (originally Etranges rumeurs) which were his individual “observations” of his contemporaries: Debussy (his closest friend), Dukas (who often helped him financially), and Roussel (who taught him the art of counterpoint). In Satie’s sketches, the first two pieces bear sub-titles: Debussy’s Idylle, with its continuous four-note bass ostinato, represents “A poet who loves nature, and says so”; whilst in Dukas’s Aubade, he had in mind “A fiancé beneath the balcony of his fiancée”, thus making it a guitar-strumming serenade. The poet in Méditation, “shut away in his old tower…on whom genius gazes with an evil eye: a glass eye”, is undoubtedly Satie himself, despite the dedication to Roussel. San Bernardo (2 August 1913) is a first version of Españaña, the last of the Croquis et agaceries d’un gros bonhomme en bois, were reconstructed from Satie’s sketchbooks in the Bibliothèque Nationale de France (like the 6e Nocturne below).

In 1918–20, before his final ballets, Satie’s music adopts a more serious tone, perhaps as a reflection of the horrors of the First World War. Beginning with his masterpiece, the symphonic drama Socrate, Satie extended this approach into his six, sparsely textured Nocturnes of 1919. The first three were conceived as a set in D major, which Satie told Valentine Hugo were “not at all bad…The first serves as a prelude; the second is shorter and very tender—very nocturnal; the third, yours, is a more rapid and dramatic nocturne. Between the three of them they form a whole with which I am very pleased.” To these Satie added the sensuous 4e Nocturne with its parallel fifths, the more austere 5e Nocturne in F, and the Sixth, with its sonorous, Brahmsian bass octaves and its masterly return to the home key of the whole cycle on its very last chord.

credits

released November 28, 2015

Project Producer • Réalisatrice du projet : Eve Egoyan

Recording Producer • Réalisateur de l’enregistrement : David Jaeger

Sound Engineer • Ingénieur du son : David Quinney

Digital Editing • Montage numérique : Peter Cook, Natasha Aziz

Digital Mastering • Gravure numérique : Peter Cook

Production Coordinator • Coordonnatrice de la production : Paulette Bourget

Notes : Robert Orledge

Notes Editor • Éditrice des notes : Lauren Pratt

Translation • Traduction : Charles Metz

Graphic Design • Conception graphique : Caroline Brown

Art Direction • Direction graphique : Eve Egoyan and David Rokeby

Recorded at Glenn Gould Studio, Toronto, July 2, 3 and 4, 2002

Enregistré au Studio Glenn Gould, Toronto les 2, 3 et 4 juillet 2002

Cover drawing by Erik Satie, “Hôtel de la Suzonnière”, by permission from the Archives de la Fondation Erik Satie Dessin de la couverture par Erik Satie, «Hôtel de la Suzonnière», avec l’autorisation des Archives de la Fondation Erik Satie Back Photo • Photo au dos : David Rokeby